Interview with master music analyst and theoretician Marianne Feenstra

Interview by Stefan Joubert

Marianne Feenstra Teaching Music Analysis at Our Annual Seminar at Sun City in 2015

A music interview with Marianne Feenstra – world-class music analyst:

From Stefan Joubert:

I had the rare privilege of studying music theory with Marianne. She is an excellent instructor and world-class music analyst. She is also an author of several books and you can find the material on feenstrabooks.com.

It was a pleasure to have her with us at our seminar in Sun City 2015. She was a real inspiration to us all!

Stefan, thank you for your invitation. It is a great pleasure for me to be able to speak to you again.

Which books would you recommend for students wanting to improve their knowledge of music theory and analysis?

Books are very much a matter of personal choice. I have always preferred writers that get to the essence of the matter quickly and easily. For learning basic music theory like note values, key signatures, intervals, scales and the other odds and ends that inform score reading, I have found the material produced by the ABRSM really good. Their explanations are clear and easy to understand.

I grew up with the series of books by William Lovelock to learn harmonic progressions, but I always (even as a student!) found them to be rather longwinded and repetitive. There are now many books – especially American ones – that do the same thing by referring to actual composed music, and those are much more user-friendly. I particularly like the series that was produced by Paul O. Harder called Harmonic Materials in Tonal Music. Volume I is excellent and easily available; the same goes for Volume 2, but it is a little harder to find. It is a programmed course for self-instruction, and when it is combined with input from a knowledgeable teacher, it is unbeatable.

When one goes further, and one starts looking at the style of an individual composer, one would choose studies about that person’s music.

You are a master at teaching music theory and analysis. I vividly remember your classes in Pretoria. You have an amazing ability to make complex theoretical concepts seem easy. What is your secret?

I have always loved seeing the relationships between chords and the way this relates to the structure that a composer has created. And I love discovering new links! I have tried to put across to my students that the music of the great composers will always be able to provide one with new insights. I remember once reading that to distinguish a great work from a mediocre piece is easy. You are quietly sitting listening, and the composer has lulled you nicely into thinking that you know what will come next – and then what you expected does not happen. And you think to yourself “Now I would never have thought of doing that.”

Every time a composer jolts you into realising that you cannot second-guess the direction of the music, you are listening to a genius at work. I try to put across that “wow!” moment when I teach.

For beginners wanting to improve their music theory knowledge, what would the first steps be to lay a proper foundation?

I don’t think one can emphasise the importance of listening to music sufficiently. And not just music that you are comfortable with, as many styles and genres that you can find. You, for instance, introduced me to the playing of Yngwie Malmsteen, and it was a real eye-opener for me. Music theory must always be related to the music that gave rise to it, and if one does not have a broad music base to which to refer, it ends up not making much sense, except on paper.

A lot of our students are adults learning to play music for their own pleasure. A number of our students are very serious about improving their musicality and want to achieve the highest possible level of success in their musicality even though it is not their primary career. As their time is limited due to (highly) demanding jobs and a solid practice regime on their instrument, what can they do to improve their music knowledge in terms of theory and analysis?

I think the best approach is to understand what you are playing. Take the time to consider the formal structure and how the keys and harmonies work together to create that structure. For example: if you are playing a piece like Claude Debussy’s Voiles, consider first all the different meanings of the title.

Then put it into context: Debussy loved the music of Chopin, and they were both brilliant pianists. Debussy must have found a great deal of inspiration in Chopin’s piano music, so one can start by looking at the texture of the work. Yes, there is a wholetone scale in the right hand, and yes, there is a pedal on B flat in the bass, but what is happening in the middle voices?

There’s a whole lot of movement, including some ostinatos that turn the piece into a masterpiece of counterpoint. Chopin was a master at creating subtleties beneath his glorious melodies, and Debussy did that too. So one of the ways to understand music is to know who inspired the composer, and in Debussy’s case, he kept saying loudly and clearly that it wasn’t the Impressionist painters, but no-one listened. It really opens one’s ears when one’s eyes see differently.

What advice would you give to students when learning to play a new piece of music? (In terms of analysis)

Oops, I ran ahead of myself in Question 4, didn’t I?

But I would add: listen, listen and listen to as many different recordings as you can, first without following the score, and then with the score. It is important to get an overall impression of the work so that you know where you are heading. From these listenings, you would be able to draw many facts about its structure, its harmonies, its mood and its texture. Then try to sight-read as much of it as you can so that you get a “feel” for it under your fingers. Then, finally, sit down and play it through slowly and correctly.

A big issue with students learning how to play an instrument is often the fact that they lack the theoretical side of music. Do you think the traditional method of learning music is suitable – i.e. one hour per week instrumental or vocal tuition with very little being paid to theory. Would it not be a far better solution to at least commit to doing two hours per week with one hour being instrumental and the other being theoretical?

I would definitely commit to a balance between practical and theory. Splitting it is possibly good for many students, but I would try to integrate the theory with the practical as far as possible by teaching the theory that is necessary from the pieces that are played. That is quite hard to do, but it is very rewarding.

Could you share a selection of exemplary compositions that the serious student of theory and analysis should study?

Now that is a difficult question!

Each great composer has something to teach us.

I would go for:

* J.S.Bach, especially the preludes from the “48” because they display almost every technique that he used in all his other works. They are also all exceptionally lovely pieces of music.

* D. Scarlatti’s Sonata in E major K.380/L.23 never ceases to amaze me with its fabulous harmonies.

* Franz Haydn‘s symphonies, which are just super, from a structural and a harmonic point of view. He encapsulates intellectual musical wit.

* Wolfgang Mozart’s just about everything! That glorious aria Reich mir die Hand from Don Giovanni? Check the words, check the scenario – the lecherous oaf trying to ‘conquer’ his employee’s bride – and one appreciates how Mozart could reflect a bully’s true character through the most innocent of melodies. And his ability to incorporate improvisation techniques into formal structures cannot be beaten by anyone (except, perhaps, by Chopin).

* Beethoven for his glorious, sweeping melodies that are often based on only the minimum of chords, and his ability to modulate using just one note. In the 5th piano concerto, I get goosebumps without fail at the link between the end of the slow movement and the beginning of the last movement.

* Schubert, if you like songs. In Der Erlkönig the way in which the 3 characters – the son, his father and the Erl King (who represents Death) – are depicted and framed by the narrator’s introduction and conclusion are dramatic coups, and the accompaniment shows what can be done using the barest minimum of material.

* Chopin. The intricacies of his harmonies and the freedom of his structures are incredible examples of creative thinking.

* Wagner’s Prelude to Tristan and Isolde. I don’t particularly like Wagner’s operas, but this prelude is a signal event in music because it caused people to stop and consider how chords were being structured, and what could be classified as ‘dissonance’.

* In the 20th century, Schoenberg’s Piano piece op. 11 no. 1 for its new sounds and approach to tonality; Stravinsky’s A soldier’s tale for reflecting the cynicism after World War I; Penderecki’s Threnody for its chilling soundscape; Samuel Barber’s Adagio for strings for its glorious celebration of the new musical language that remained a constant factor when all other ‘innovations’ became old hat; Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet for its celebration of the partnership between music and ballet, and its sheer beauty.

According to Wikipedia, in 1700 there were 600 million people on the face of the earth. Today we have 7 billion. A larger population did not necessarily lead to better music… Johan Sebastian Bach (and others) faced far less competition than we have today, yet music composition is certainly not better today. This probably means that a larger population does not necessarily mean more success. What is your theory on this?

I think we are sometimes blinded by what is pushed as “classical music” and “contemporary” and all sorts of words like that.

“Experimental” pieces are important because they open up new ways of thinking, but they are just that: experimental. It is also rather interesting to see that many of the great composers (especially in the 20th century) pushed a certain aspect of their style to the limit and then abandoned it.

I think of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, for example, which changed the way people understood rhythm, but Stravinsky then applied what he himself had learnt in far more conservative, and certainly more beautiful, works. The same goes for Richard Strauss. Once he had written the operas Salome and Electra he turned his back on that style (which influenced many of his younger contemporaries, including Schoenberg) and gave us the ultimate Viennese opera, Der Rosenkavalier.

There are many composers who are writing extraordinarily lovely works, and the latest generation (at least in SA) are exploring glorious sound combinations, much of which was inspired by Peter Klatzow. So I think rubbish is all around us; we must look for the gold!

How would you approach teaching adults versus professional students?

Adults need to be challenged at a different level to professionals.

Professionals are looking towards building up a huge repertoire which can be played without errors, and they need enormous physical as well as emotional and intellectual stamina. I read just today that the Rachmaninov 3r piano concerto, for example, has 30 000 notes for the pianist to memorise – and that could be just one of 15 or more concertos that a professional pianist could play at a day’s notice, without taking into consideration the sonatas and other solo works required.

An adult needs (I think) a nice wide repertoire of which several pieces can be played from memory and the rest from music. Perfection is not necessarily the top of their list; they know that they would probably never play like a professional, but they want to get as close as they can.

Any secrets of success that you would like to share with our readers?

The renowned golfer Gary Player, when someone said “Gosh! That was a lucky shot!” retorted “Yes, the more I practise, the luckier I get.” Hard word is the only secret that there is.

Do you think that beginner students underestimate the importance of learning music theory?

They probably do.

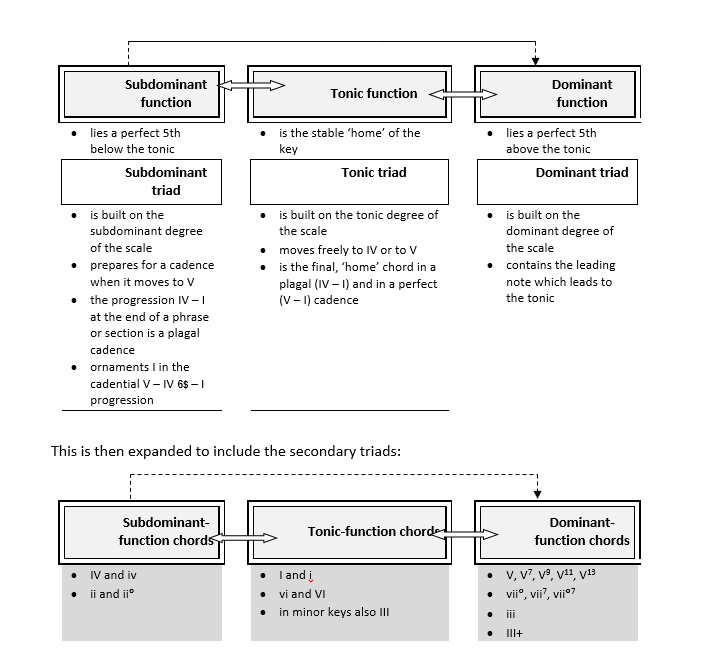

Could you share ‘the inherent movement of chordal progressions’ with our readers? (Tonic/Subdominant/Dominant – categorisation of movement)

I have a useful diagram that I like to use. It encapsulates the whole idea.

Out of the following qualities – ‘brilliance, ingenuity or faithfulness’ – which do you value most in a student and why?

I would value ‘faithfulness’ and interpret it to mean ‘faithfulness to oneself, to one’s own dreams and hopes’. Nothing can stop a student when they are faithful to themselves.

What is the one thing that a student can do daily improve his or her theoretical knowledge?

The moment you hear something new, something ‘different’, try to find out what it is, and how it works.

There is generally a set methodology for practising an instrument. What would be a good practice schedule for musical theory and analysis?

Read, do, and understand.

South Africa must have a huge variety of new music enthusiasts and students. You have played a major role in helping many students develop their musicality. What is the future for music education in South Africa?

That is quite a difficult question to answer. Some teachers are very resistant to any change and want to continue doing things the way they were taught. The new curriculum statement allows for a great deal of freedom and for innovative teaching, and this is going to be difficult to pull off.

I have recently co-written two sets of books for our Grade 10 (about O levels) and Grade 11 (first year of A levels) curricula, and am finding some of the resistance coming from the very people who set the curricula – as though they did not realise just how radical and innovative they were being, and now find it challenging to follow through. The learner numbers are falling fast, and so are the student enrolments at tertiary level, and I find that rather disheartening. South African music has a lot to offer the world.

You have recently started Feenstra Books, what are your plans for the future?

To publish more educational material, particularly at university level. We are far too reliant on books from the USA, and their perspective does not match ours at all. We need to find a pride in our musicians and composers.

Is it possible to purchase your books directly on your website (http://www.feenstrabooks.com/)?

Unfortunately not a direct purchase due to challenges encountered with the payment systems. But one can certainly order online and then pay, either using a bank transfer or PayPal.

Thank YOU, Marianne, it was a real pleasure to conduct this interview with you. Thank you also for your kindness and excellent instruction that we have received at the music seminar in Sun City 2015. We were all very inspired!

Interview conducted by Stefan Joubert

Marianne Feenstra is a world-class musician, theorist, instructor and music analyst.

She has an uncanny understanding of music and she has the rare gift of being able to make the complex simple. She is a true gift to music and all students can testify to her excellence and outstanding abilities when it comes to both analysis and tuition. Read her full CV here